Bitcoin Is No Longer the Energy Threat, but AI Is Becoming One

In 2024, Bitcoin consumed between 173 TWh and 228 TWh of electricity. Meanwhile, data centers consumed an estimated 415 TWh, but faced far less scrutiny. This shift reflects a difference in how people experience each technology. AI tools such as ChatGPT, Gemini, and Copilot reached billions of users and created a sense of direct personal value. Bitcoin, on the other hand, is primarily associated with speculation or investing and remains outside most people’s daily habits. As a result, AI expanded its energy consumption without the public pressure that once surrounded Bitcoin. It did so while drawing from the same global pool of power infrastructure that is now reaching critical limits.

This article builds on insights shared with CryptoRank by Alex de Vries from VU Amsterdam and Digiconomist and by Jon Ferris from LCP Delta. Their expertise highlights a structural tension that is becoming impossible to ignore. AI requires rapid access to large amounts of electricity, which grid operators may struggle to keep pace with. Bitcoin miners already control many of the world’s largest private power connections. These conditions are pushing the two sectors into direct overlap and are creating new incentives for mining operators to redirect their infrastructure toward AI workloads.

Bitcoin’s Energy Consumption: The Reality Check

Bitcoin’s energy use has been discussed for years, but the narrative around it has often moved faster than the data. Early forecasts warned that Bitcoin could overwhelm national power grids, yet the network has settled into a predictable range shaped by transparent economics and increasingly clean electricity sources.

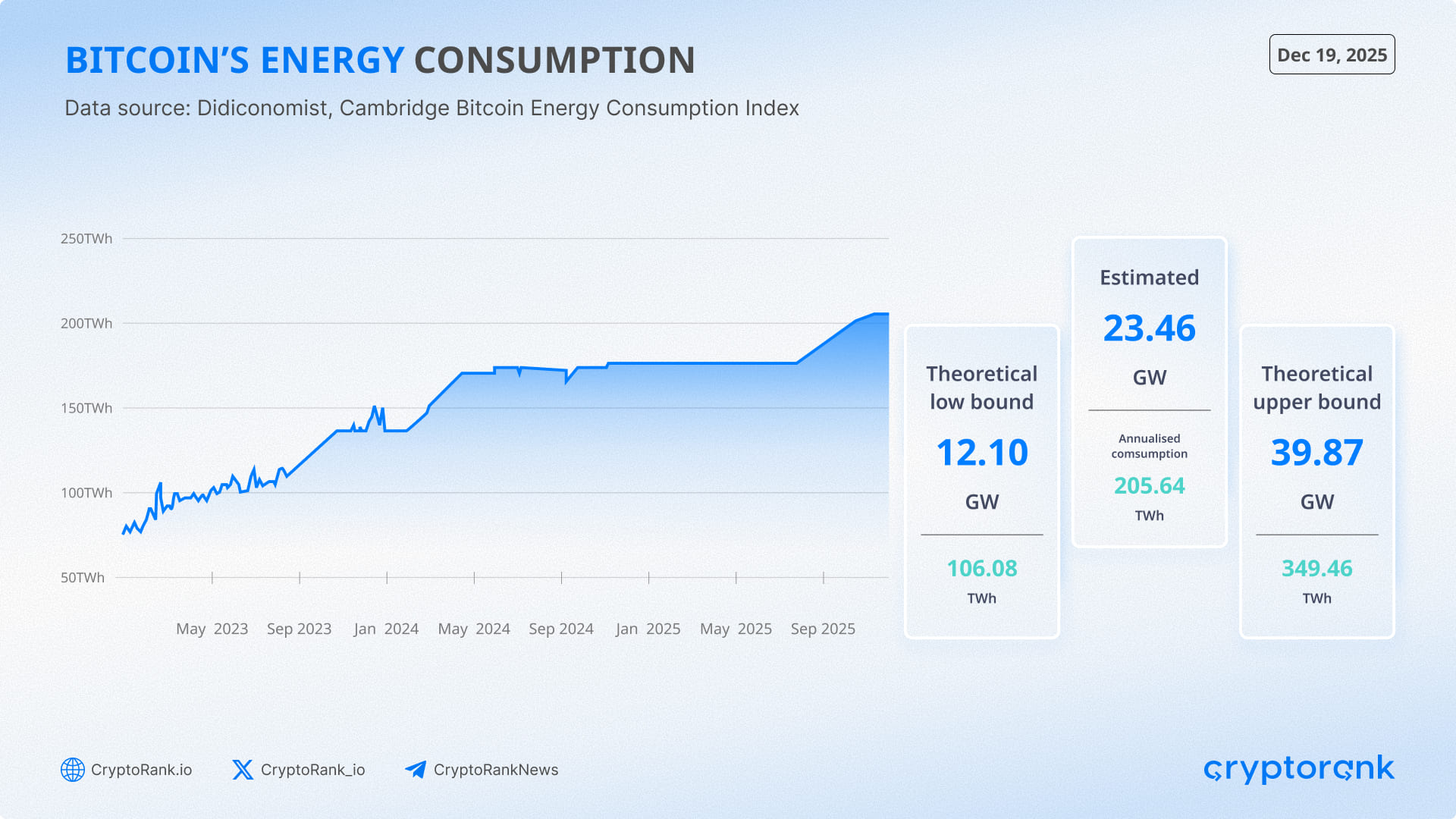

Currently, the Bitcoin network consumes about 205 TWh per year, according to two popular models, the Cambridge Bitcoin Electricity Consumption Index and Bitcoin Energy Consumption Index. This places Bitcoin at roughly 0.8% of global electricity demand, comparable with Poland’s annual 224 TWh. The scale is meaningful, but it is far smaller than the early predictions that shaped public perception in 2017-2018. Those predictions assumed exponential growth, yet mining followed the economic limits of its reward structure instead.

Source: digiconomist.net/bitcoin-energy-consumption, ccaf.io/cbnsi/cbeci

The Bitcoin network is also transparent in how its energy use can be estimated. The hashrate is public and updates continuously. The difficulty adjustment shows how much computational power is competing for block rewards. Higher hashrate signals higher aggregate power draw, and difficulty keeps the block interval stable regardless of how many machines are active. This relationship allows models such as Cambridge’s to link observable network data with realistic hardware efficiency assumptions. It also means Bitcoin’s power demand can be approximated with simple and verifiable inputs.

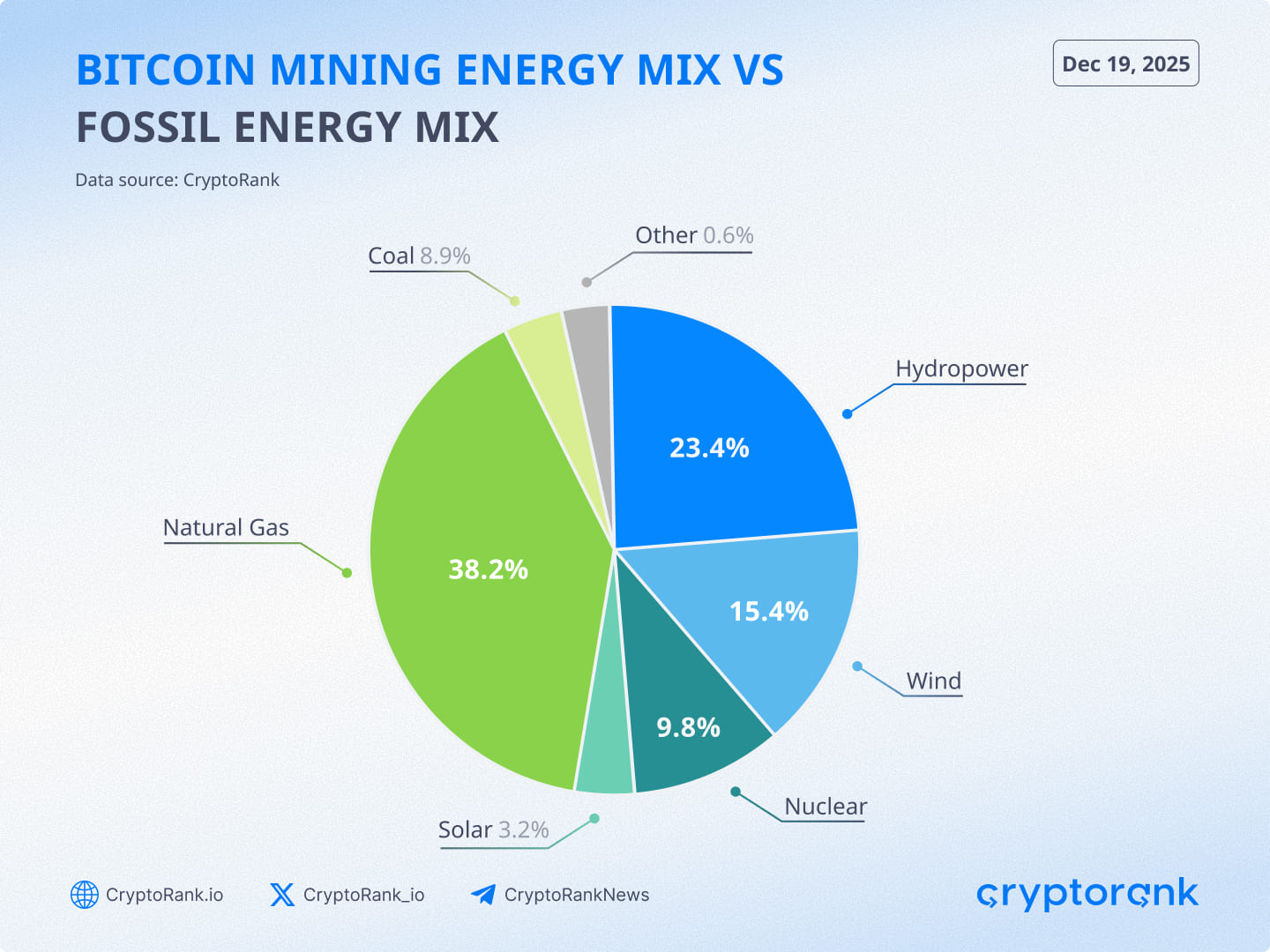

When speaking of Bitcoin’s massive consumption, it is important to understand the composition of Bitcoin’s energy mix. The network draws about 52.4% of its electricity from sustainable or low-carbon sources: hydropower, wind and nuclear, and solar. The remaining 47.6% comes from fossil fuels. This distribution improved after China’s 2021 mining restrictions pushed operators into regions with cleaner grids or lower-cost stranded supply. This restriction, however, has been softened recently, but China’s energy production has already moved towards renewables.

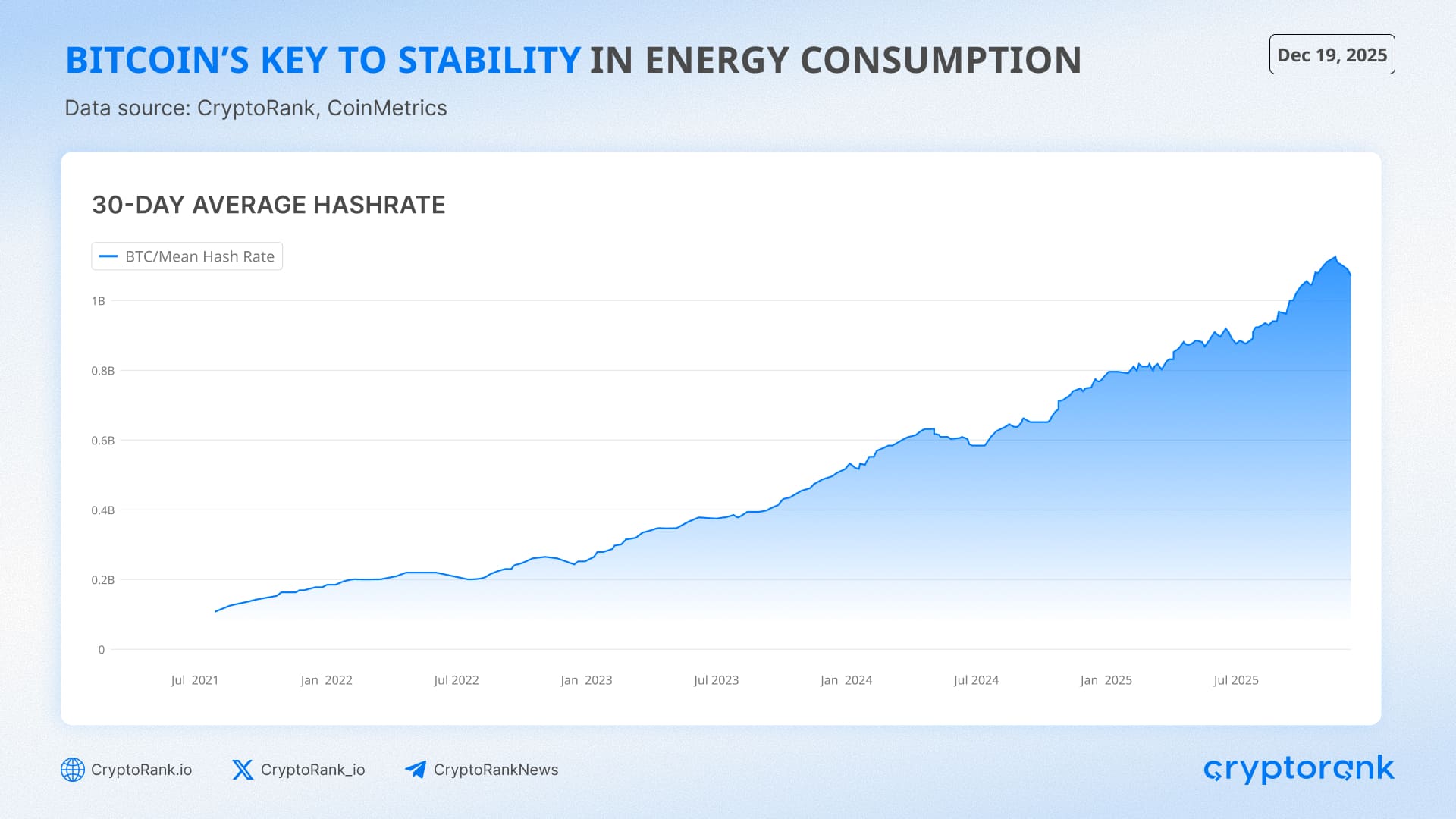

Bitcoin’s Key to Stability in Energy Consumption

Bitcoin’s long-term stability comes from its economic design. The Bitcoin network undergoes the Halving event every 4 years, which cuts mining rewards by half. This is what early forecasts forgot to account for properly. Energy use can only grow if revenue grows faster, which creates a natural limit. Also, technical progress has not stalled, and equipment improvements have been substantial in recent years. Alex de Vries explained this relationship by noting that “the economics of Bitcoin are so transparent that you can estimate its power use with simple inputs like price and hashrate.” His point reflects why the network does not follow an unchecked growth path.

Bitcoin’s operational flexibility also affects its overall impact. Mining facilities can reduce their load in seconds because ASIC miners can be switched off instantly without interrupting any ongoing process. This makes them useful participants in demand-response programs in regions with variable renewable energy. Several large miners in Texas earned curtailment revenue during periods of grid stress in 2025, which helped balance supply and demand during extreme weather.

Artificial Intelligence: The Key Energy Market of the Current Age

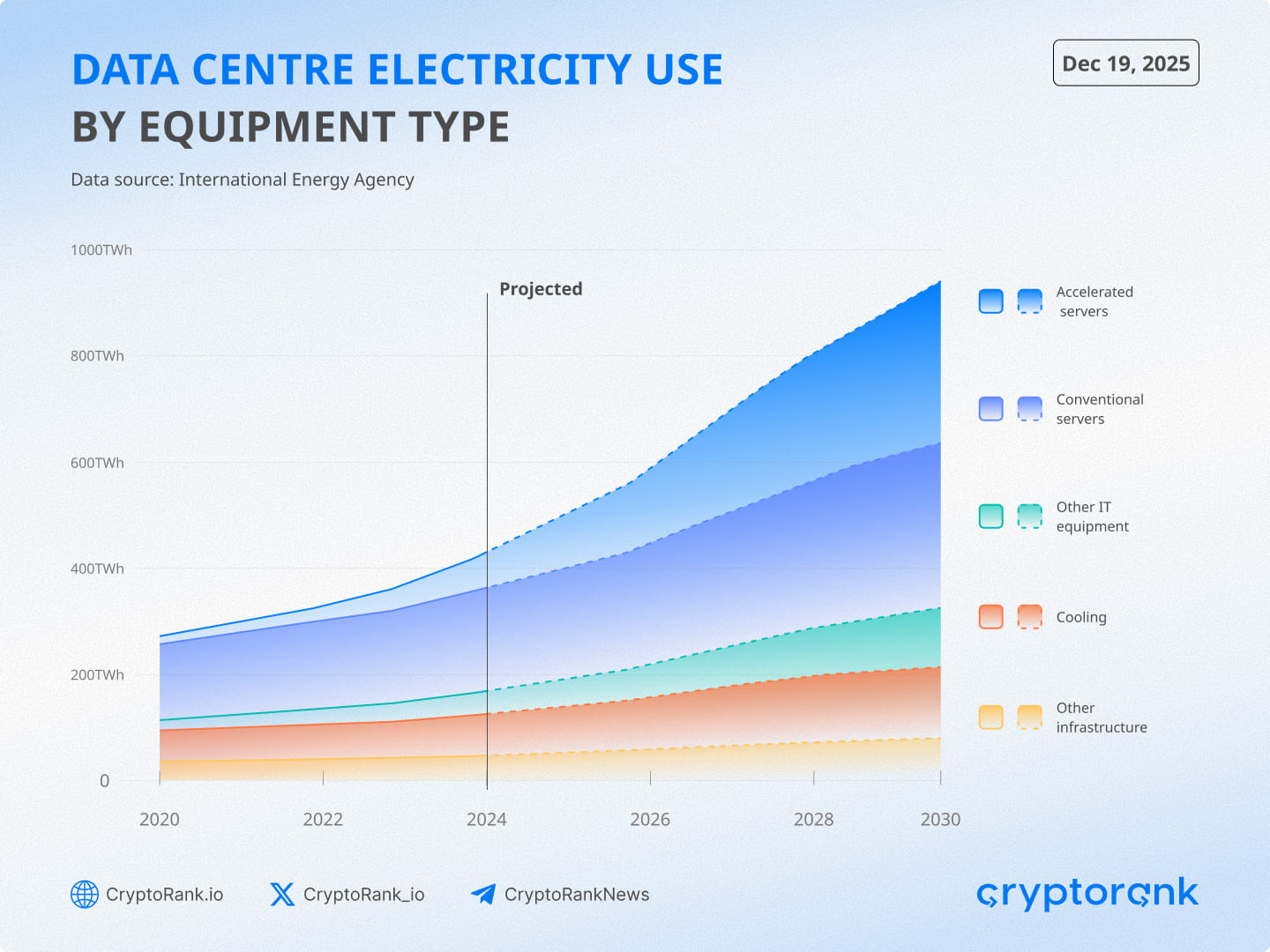

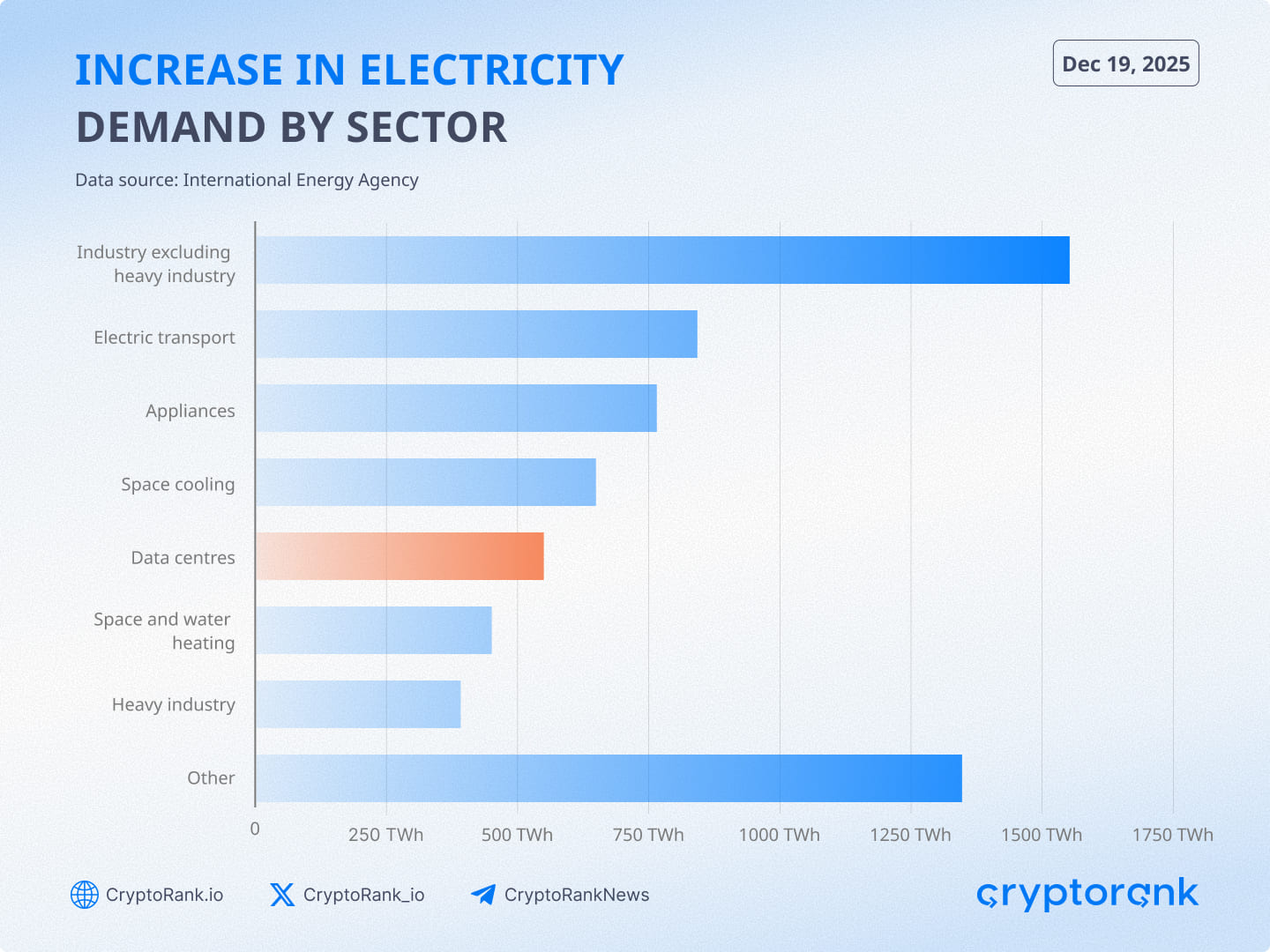

Artificial intelligence has become the fastest-growing source of new electricity demand, and its rise is reshaping power markets at a pace that no previous digital technology has matched. Data centers consumed an estimated 415 TWh of electricity in 2024, which is roughly twice the scale of Bitcoin’s annual footprint. In the United States alone, the figure reached about 183 TWh, or 4.4% of national demand. Moreover, this figure is projected to double over the next five years.

This surge is driven by two forces that reinforce one another. Training requires enormous GPU clusters capable of running continuously for weeks, while inference has become a constant background load that grows every time AI systems are built into search engines, productivity software, voice assistants, and enterprise workflows. In the coming years, data centers will likely consume the same amount of energy as global appliances.

Source: iea.org/reports/energy-and-ai/energy-demand-from-ai

Unlike Bitcoin, AI’s electricity use is difficult to measure. There is no public indicator similar to hashrate or difficulty, which makes real-time tracking impossible. Most data comes from indirect signals such as corporate electricity contracts, the size of new data centers, and the volume of advanced chips entering the market. Even the widely cited energy announcements from Google and Microsoft focus on future infrastructure like nuclear projects or large power purchase agreements rather than present consumption. As Jon Ferris notes: “Tech companies do not disclose much, so there is no reliable source that tracks real-time energy consumption for AI”.

AI is on track to account for nearly 40% of global data center electricity use by the end of 2025, and its share is expected to rise sharply throughout the next decade. Bitcoin follows a different trajectory because its energy use is tied directly to market economics. According to MiCA, Bitcoin’s consumption could reach about 500 TWh if the price climbs to $250K after the halving. In a highly optimistic $500K scenario, annual demand could approach 1000 TWh. If Bitcoin’s price does not rise significantly, its electricity use is likely to remain close to current levels.

Comparison of Data Center and Bitcoin Energy Consumption Forecast

|

Data Center Energy Consumption |

Bitcoin Energy Consumption |

||

|

2025E |

2030F |

2025E |

2030F |

|

536 TWh |

1065 TWh |

200 TWh |

~500 TWh at $250K per BTC ~950K TWh at $500K per BTC |

Source: CryptoRank, Deloitte Insights, MiCA

Behind the scenes, AI relies on a supply chain that is far more energy-intensive than the user experience suggests. The majority of high-end GPU and accelerator production occurs in East Asia, where electricity grids remain heavily dependent on fossil fuels. Taiwan, South Korea, and Japan all operate with energy mixes in which fossil sources range from about 58% to more than 80%. Once deployed, these chips continue to draw substantial power. Training frontier models requires uninterrupted operation of thousands of accelerators, while inference multiplies demand across millions of daily interactions. As AI systems become embedded in more services, the cumulative effect has created a near-continuous load on global data centers.

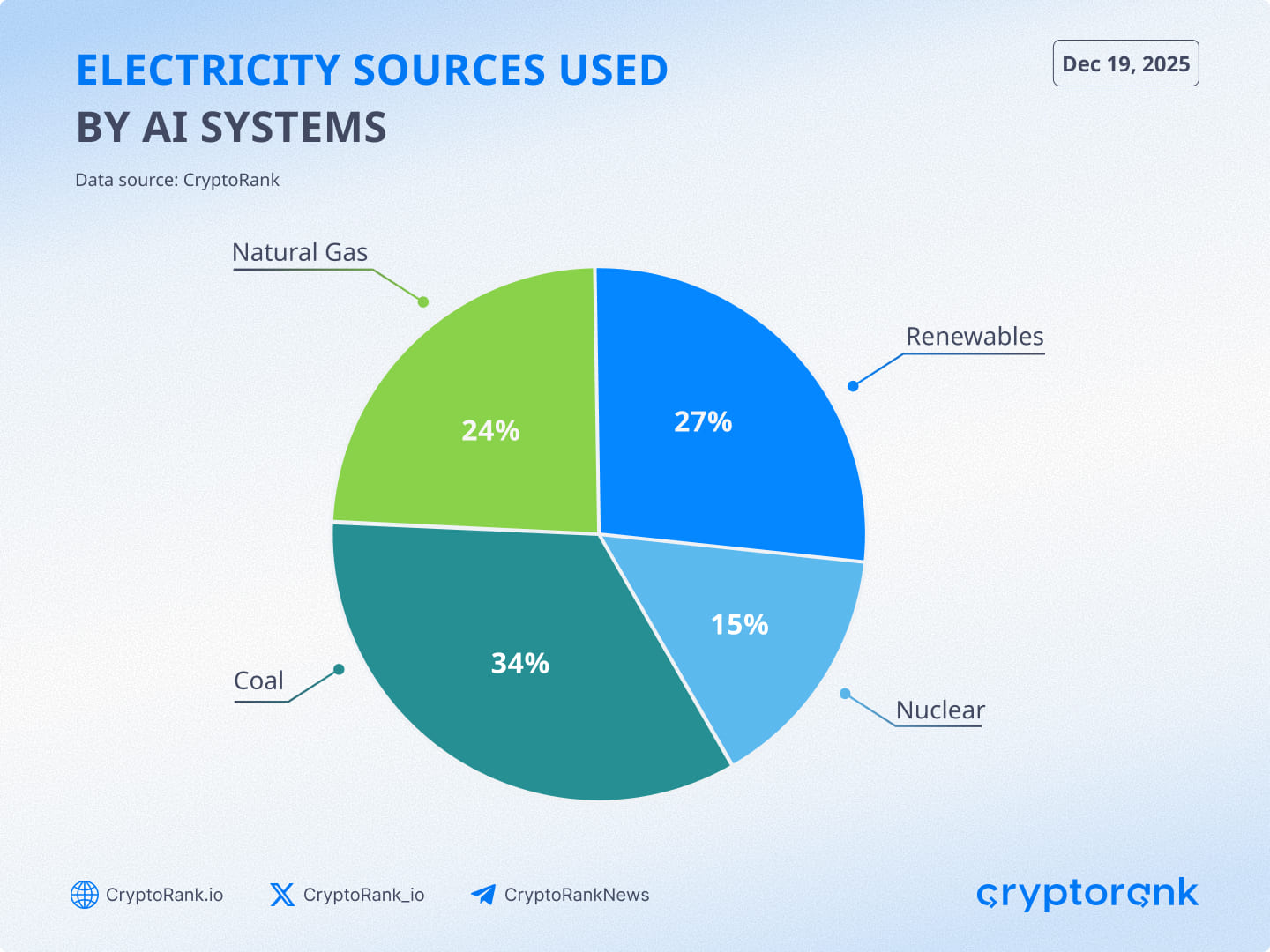

Artificial intelligence also relies on a far more carbon-intensive energy mix than Bitcoin. Only about 42% of the electricity used for AI workloads comes from clean sources, a much lower share than the renewable and low-carbon contribution within Bitcoin mining. The rest of AI’s energy profile is split across renewables, nuclear, coal, and natural gas, and is dominated by fossil fuels, which remain central to both the manufacturing and operation of AI hardware. As a result, AI carries a larger embedded carbon cost at every stage of its lifecycle, from chip fabrication to model training and inference.

The rapid expansion of AI is now pressing against the physical limits of electricity infrastructure. Grid operators report unprecedented congestion in key regions. In the United States, requests for new data center connections have surged from a small number per year to thousands, far exceeding planning capacity. Securing a high-power interconnection can take a decade in many areas. Dublin’s data centers already consume most of the city’s electricity, which has led to strict limits on further growth. According to Jon Ferris: “The power demand of AI is huge and could reach about 1% of global electricity consumption by the end of this year, but there are not many power grids that still have that much power left”.

Despite these constraints, AI continues to be viewed as a technology worth accommodating, both by the public and by policymakers. Daily use of AI services has made the technology feel familiar and beneficial, which has softened scrutiny of the sector’s growing energy footprint. This stands in sharp contrast to Bitcoin’s experience during its early growth, when energy use became central to the broader debate around cryptocurrency. AI has so far avoided that level of criticism even as its electricity demand accelerates at a far faster pace. Whether this goodwill persists will depend on how quickly energy systems can expand and how clearly the industry communicates the real cost of scaling intelligent computation.

Opportunity for Bitcoin Miners

AI has created a sudden global demand for electricity that the grid cannot meet. New data centers face long delays for power connections, and many regions have already exhausted available capacity. Bitcoin miners already control large interconnections, high-capacity electrical infrastructure, and industrial sites built for continuous computation. These assets have become valuable at a time when access to power matters more than access to capital.

Several major miners have already begun shifting part of their operations to AI workloads. Existing mining campuses can be adapted for GPU hosting faster and at far lower cost than building new AI facilities from scratch. Power contracts, cooling systems, and land rights are already in place. Revenue from AI inference or training can exceed mining margins, which gives operators a clear financial reason to diversify.

Mining also gives companies operational flexibility that traditional data centers cannot match. ASIC fleets can be powered down instantly, allowing sites to participate in demand response programs while running stable AI clusters in parallel. This hybrid approach helps operators capture higher returns while improving the reliability of local grids.

Bitcoin miners have spent years securing the assets that AI companies now lack. They have the power, the locations, and the infrastructure to deploy large-scale compute quickly. As AI demand accelerates, miners are positioned to become key suppliers of the next wave of digital infrastructure.

DePIN also offers miners a new avenue for growth. Decentralized physical infrastructure networks allow compute to be supplied across distributed hardware rather than relying on single hyperscale sites. This model fits well with miners who prefer to support decentralized networks. Telegram’s recent launch of a decentralized AI network on TON shows how AI workloads can be supported in a distributed way, creating opportunities for miners to contribute compute and earn new revenue streams.

Conclusion

The global debate on digital energy has shifted. Bitcoin’s electricity use has stabilized and become increasingly transparent, while artificial intelligence has grown into the most powerful new driver of demand on modern grids. AI’s scale, opacity and fossil-heavy footprint present challenges that are only beginning to surface. Bitcoin miners now find themselves in a position few anticipated. Their existing power access and operational expertise align directly with the needs of AI companies that are constrained by limited grid capacity. As energy systems adapt to the accelerating rise of intelligent computing, mining operators are becoming unlikely but essential contributors to the next phase of digital infrastructure.